25 / 12 / 03

What 210 Million Yuan Buys: Robot Dogs and a Student’s Breakdown

中文版本请点击此处

The Magnolian has published a statement regarding this article. Click here to read.

At a 210-Million-Yuan School, Students Struggle for Basic Support

At a 210-Million-Yuan School, Students Struggle for Basic Support

Investigation Examines Xiwai's Priorities and Student Wellbeing

I. Through the Classroom Door

The classroom door wasn’t fully closed. Through the gap, I could see Mr.Zheng gesturing as he addressed the teachers in an ordinary Friday afternoon meeting, his voice carrying that particular confidence administrators use when they believe students aren’t listening. I had come to deliver documents. My hand was on the door handle. I should have knocked, handed over the folder, and left.

Instead, I stayed. Opened my notes, and started writing.

“10年级R班:最烂的一个班级,情商智商都有问题,学习基础也有问题。”The words landed like stones in water. Grade 10, Class R: the worst class, with emotional intelligence and IQ problems, with learning problems.

Mr.Zheng, in his capacity as the Moral Education Director of Shanghai Xiwai International School’s International High School Department, was explaining the enrollment crisis to the assembled faculty. It was March 29, 2025. Student attrition was severe, he said. The school needed better marketing, a more “positive, sunny image.” Teachers needed to stop complaining, attend recruitment fairs, bring in new families. He was teaching them, essentially, how to sell a product. The students-some of us, anyway-were the defects.

I was 17 years old, I had been managing depression symptoms with medication for three years. I had spent the previous year drafting a constitution for our student government, creating what I believed would be a democratic structure with real procedural protections, real student voice. I was good at school. I believe in school. I thought the rules mattered.

II. The Breakdown Bought using 210 Million

Standing outside that door in March, listening to how a school administrator actually talked about students when he thought we couldn't hear, something shifted. Not dramatically. Not all at once. Just a small crack in the foundation of how I understand the institution I had attended since fifth grade.

Six months later, the same man would systematically dismantle the student organization I had built. The crack would become a chase. And I would find myself in a psychiatrist’s office at Tongji Hospital, receiving a new diagnosis: bipolar disorder with severe depression, severe anxiety, and mild mania. The doctor would explain that prolonged stress and trauma can trigger underlying conditions, and that what I was experiencing was real and serious.

The school—despite generating annual tuition revenue of over 210 million yuan from approximately 3000 students—would do nothing.

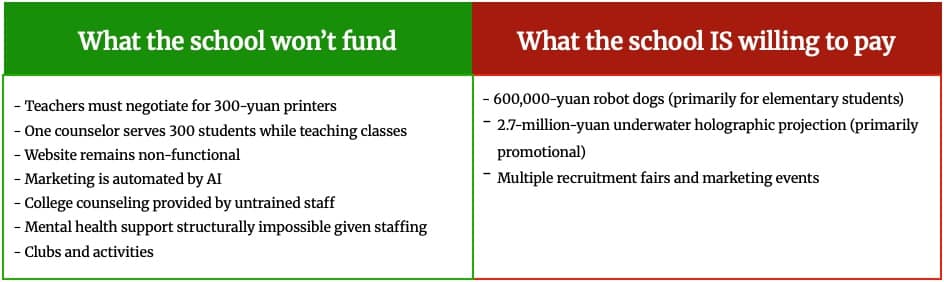

My family still isn’t fully aware of the diagnosis. I manage my medication, see my psychiatrist, and write this article because I have spent six years believing in Xiwai’s stated mission. And because I now understand that my breakdown wasn’t personal failure. It was a predictable outcome of an institution that systematically chooses marketing over mental health, control over care, and spending 3.3 million yuan on robot dogs and holographic projections while refusing to give teachers 300-yuan printers.

III. The Collapse of Student Government

The formal collapse came on a Tuesday afternoon in late September, the day before our Student Life Organization elections. The nomination period had closed. Candidates were finalized. Three hundred paper ballots sat printed and stacked in the library. The process had been transparent, procedural, exactly as outlined in the constitution I had spent a year writing, and the student body had ratified.

Then Mr.Zheng texted me on WeChat and informed me that four students who had missed the nomination deadline must be added to the ballot anyway.

I explained that this was impossible. The ballots were printed. More importantly, it violated the constitutional procedures that governed our procedures, public and fair.

He refuted. “规则是你定的,你就可以做一些改变啊。” The rules were set by you, so you can make changes.

I tried again, citing specific constitution articles. He said. “世界上任何一项规定,哪怕是宪法,不都在改吗?” Any rules in the world, even constitutions, gets amended, right?

The logic was dizzying. Yes, constitutions can be amended—through established amendment procedures, with proper process and ratification. Not because an administrator found them inconvenient on a Tuesday afternoon.

A Lesson in Power

He continued. “选你之前没有这些章程的,都是老师推荐优秀学生的。你不就做了一个章程而已吗?” Before you were elected, there was no constitution. Teachers just recommended good students. You just made a constitution, that’s all.

The year of work—the drafting, the revisions, the student debates, the ratification—reduced to a personal whim. Something I had “just made,” and therefore something that could be unmade whenever inconvenient to someone with more power.

I kept pushing back. I was the student body president. This was literally my job: to defend the procedures we had established. And that's when Mr. Zheng stopped arguing and started educating me about power.

“你别忘了啊,中国的选举永远都不是民主选举,它是民主集中制…所有的活动,政治活动、选举活动都是领导在控制和操作的,明白吗?” Don't forget, elections in China are never democratic elections. They are democratic centralism. All political activities and elections are controlled and manipulated by the leadership. Understand?

I suggested that a student organization might operate differently from a national government. He said. “美国美国的选举就民主了吗?拉票对吧,马斯克给这么多钱去拉票,这是民主吗?” Are elections in the United States democratic? Lobbying, right? Musk gives so much money to lobby—is that democracy?

The message was explicit: democracy is a sham everywhere. Rules are for the naive. Power is what matters. And he had it.

The Final Word

When I still wouldn't concede, he shifted tactics again. “你呢?还年轻,你才十几岁。毕竟我在这个学校里,我待了15年了,我年龄也是50多岁了.” You're still young. Just a teenager. I've been at this school for 15 years. I'm over 50.

He deployed an idiom about execution—“杀人不过头点地啊”—suggesting that my principled stand was an act of merciless cruelty. That by defending the rules, I was somehow being unreasonable, inflexible, and harsh.

Finally, he stopped pretending this was a conversation between an advisor and a student leader. “我毕竟还是高中国际部的德育主任吧。你不管是学生会还是什么,你们受不受这个德育领导的那个领导啊?” After all, I am the Moral Education Director. Are you or are you not under the leadership of the Moral Education Department?

“我现在就告诉你,我就有这个权利,有这个能力,让他们4个学生最后加在里面去参与竞争.” I'm telling you now: I have the right and the ability to get those four students added to the competition.

He concluded by announcing that student leadership appointments would no longer be decided by students. They would be decided by him, Principal Enrico Piccinini and Director Monica Pan, with student input considered as “suggestions.” The SLO constitution, the electoral process, the entire year of building something that might give students real agency—all of it subject to administrative veto whenever convenient.

I was then later on blocked by Mr.Zheng on WeChat. The ballots? Voided.

IV. The Body Keeps Score

I went back home. I typed up everything he had said while it was fresh. Next morning, I drafted a formal complaint: 10 pages, with specific constitutional violations cited, intimidation tactics documented, the abuse of authority outlined in careful detail. I submitted it to Principal Piccinini through official channels and waited for a response.

Article 42 of the Education Law of the People's Republic of China grants students the right to 'lodge a complaint' against infringement of their rights by school authorities. My October 2025 formal complaint exercised this legal right, documenting constitutional violations and administrative overreach.

Piccinini did respond. He was supportive, sympathetic. Multiple teachers would later tell me he was the best principal they had worked with, the main reason many stayed at Xiwai despite everything else. But by that point, I was drowning. College applications consumed every free hour. My anxiety had become unmanageable. And something else was happening that I didn't have words for yet.

My emotions began cycling in ways I couldn't control. Intense, nearly manic productivity for hours, then paralyzing despair. I started experiencing severe headaches and stomach pain—not from any digestive issue or neurological problem, but from psychological distress manifesting physically. The school would later demand medical documentation proving I had a brain disorder or stomach disease, unable or unwilling to understand that somatic symptoms are a feature of mental illness, not a separate condition requiring separate diagnosis.

And I became afraid to come to school. Not because of academics. Not because of social pressure. Because I was terrified of seeing Mr. Zheng in hallways, of encountering posters for the Student Life Organization I had built, now reduced to what it had been before: EMAP, an acronym of bland adjectives Mr. Zheng had coined years ago, signifying nothing except administrative control.

In October 2025, a psychiatrist at Tongji Hospital affiliated with Tongji University gave the diagnosis that explained why my brain had stopped cooperating with my intentions: bipolar disorder, with severe depression, severe anxiety and mild mania.

I left with a prescription and a diagnosis. But also a question: How did an institution with over 210 million yuan in annual tuition revenue, hundreds of staff, stated commitments to student wellbeing and “holistic education,” allow this to happen? And how many others had it happened to?

V. A Pattern, Not an Exception

I already knew the answer to the second question. I had reported on it myself. And once I started looking beyond my own experience, the pattern was everywhere.

In January 2024, nearly two years before my diagnosis, I published an investigation in The Magnolian documenting Xiwai's mental health failures. The findings were stark. An estimated 34% of students in our department had experienced mental health issues severe enough to require extended leave. Students described a “culture of silence and denial” where psychological struggles were met with skepticism rather than support.

One student, Wanke Yang, told me she had been “questioned over and over again" by administrators who “made me feel like I was making it all up.” She eventually dropped out.

My emotions began cycling in ways I couldn’t control — manic productivity followed by paralyzing despair.

The State of Mental Health Support

At the time of that article's publication, the school had no effective mental health counselor at all—a direct violation of Shanghai Education Bureau mandates requiring licensed mental health professionals in every school.

Nearly two years later, we have one licensed counselor. Xiaowei Zhang is, by all accounts, an excellent, dedicated professional. She serves approximately 300 students in our department while simultaneously teaching multiple classes.

The American School Counselor Association recommends a maximum ratio of one counselor to 250 students for general academic counseling. For mental health specialists, the recommended ratio is far lower. We have one person attempting to provide mental health support to 300 students while maintaining a teaching load. The structural impossibility means genuine, sustained support remains functionally out of reach for most students who need it.

Even official state laws prompt actions, under Article 16 of the Mental Health Law of the People's Republic of China, schools are required to employ counselors and provide mental health education. The 2015-2020 National Mental Health Work Plan specifically mandates that elementary, intermediate, and high schools maintain psychological counseling offices with dedicated staff.

VI. Where the Money Goes (and Where It Doesn't)

The gap between public commitments and actual resources could not be starker. And that gap extends far beyond mental health services.

Multiple teachers have confirmed—through separate, independent conversations I later cross-verified—that faculty cannot access printers without negotiating them intoemployment contracts. I initially assumed this was an exaggeration. Then a second teacher mentioned it. Then a third. Only department heads receive printers. For a device costing roughly 300 yuan on Taobao—a tiny fraction of one student's annual tuition—this has been bureaucratized into a contractual privilege. I eventually donated my own printer to a teacher who needed one.

Meanwhile, at that same March 29 meeting where Mr. Zheng disparaged an entire class of students, he proudly announced recent purchases: a 600000-yuan robot dog and a 2.7-million-yuan underwater holographic projection system for marketing and recruitment. They are used primarily by elementary students—not the high school that paid for them—serving mainly as showpieces during campus tours. Together, that's 3.3 million yuan—enough to fund 11,000 printers, or multiple full-time counselors, or a comprehensive mental health system with proper staffing.

The Website No One Will Fix

Consider the school's website: xw.sjedu.cn. It is outdated, clunky, and contains incorrect information. For a school competing in Shanghai's international education market, where families make 120,000-yuan-per-year decisions, this undermines credibility and recruitment. A teacher with professional web design experience—someone who has a professional personal website—offered to redesign it. The IT department refused, claiming the content management system was “too complicated.”This is demonstrably false. The site runs on basic CMS architecture, functionally equivalent to Microsoft Word in complexity.

Marketing Over Substance

Marketing and communications reveal similar dysfunction. The official WeChat account increasingly publishes AI-written content—juvenile, unprofessional prose inappropriate for an institution claiming international standards. Some human-written posts are genuinely excellent, demonstrating that capable people exist. But there is no consistent strategy, no editorial standards. When I complained about AI-written posts on my personal WeChat Moments—not tagging the school, just expressing frustration to friends—I was called to meet the “official account lady” at 10 p.m. Protecting image mattered more than addressing underlying problems. Till this point, I still couldn't find out how my post in my personal WeChat account got seen by the Headmaster Dr.Lin.

Perhaps nowhere is the resource scarcity more visible than in college counseling—though here the problem isn't the counselors themselves. Our college counseling department, staffed by two dedicated professionals serving nearly 300 students, works extraordinary hours and has been genuinely supportive. They took extra time with me, provided thoughtful guidance, and clearly care about student outcomes. The issue is structural: two people cannot adequately serve 300 students preparing for international university admissions, a process that requires intensive, individualized attention.

This understaffing creates gaps that get filled by people without appropriate training. I spent months agonizing over whether to apply Early Decision to Northwestern University.

My family's financial constraints made this high-stakes. Early Decision is binding—if accepted, I must attend regardless of financial aid offered. I was leaning against ED, wanting to preserve flexibility and compare offers.

My homeroom teacher—who despite lacking professional college counseling credentials was involved in advising students—responded: "You don't have much of a chance anyway.”

Not constructive feedback. Not realistic assessment delivered with empathy and alternatives. Discouraging feedback delivered without constructive guidance or empathy, repeated multiple times. After four years of documented achievement—leadership, investigative journalism, community impact—I was told repeatedly I wasn't good enough by someone without the professional training to make such assessments. The message wasn't just discouraging; it revealed how resource scarcity forces unqualified people into roles they shouldn't be filling, ultimately harming students who deserve better.

VII. What the Teachers Say

These are not isolated incidents. They reflect patterns visible when examining what current and former staff say with anonymity's protection.

On Glassdoor, where employees review Xiwai International School, comments reveal consistency. “This place was a nightmare to work in and I advise anyone against working there,” one former teacher wrote. “Obscenely long hours for low pay, ungrateful kids, terrible management who don't appreciate their staff at all.”

Another noted communication breakdowns and “intercultural misunderstanding” in the bilingual structure, where administrative directives get lost or distorted in translation.

The school maintains a 3.6-out-of-5 rating on Glassdoor, seemingly respectable in isolation. But read reviews carefully and patterns emerge. Praise focuses almost exclusively on individual teachers and staff “autonomy.” Criticism focuses on management, resources, institutional dysfunction. Foreign staff describe feeling “protected" by middle management from “the most annoying things that might appear in bilingual schools in China”—a telling admission that deeply problematic aspects of institutional culture require active protection.

What emerges from reviews, from conversations with current and former students, from my six years' experience, is an institution where dedicated teachers and talented students struggle to accomplish meaningful work despite, rather than because of, the administrative structure. Good people exist at every level of Xiwai. But good people cannot, alone, compensate for systemic dysfunction, resource starvation and misaligned priorities.

VIII. Following the Money

This returns us to the fundamental question: Where is the money going?

The arithmetic is straightforward. Tuition ranges from 10000 to 120000 yuan per student annually. Enrollment across all divisions approximates 3000 students, yielding annual revenue of 210 million yuan. Even accounting for facilities, salaries and operations, this is substantial budget. This is not a poorly resourced institution scraping by, but an organization with significant financial capacity is making deliberate choices. 600000 yuan for robot dogs itself is already an unrealistic figure; not many products on the market are this expensive. But even if it is false, the fact that Mr.Zheng provides fabricated information to the teacher and establishes arguments on it is troubling enough; it displays the possibilities for other miscommunications.

The Cafeteria Workers

Those choices become visible not just in what the school funds, but in what it tolerates. In mid-November 2024, I investigated the third floor of the school cafeteria—a space with a stage used occasionally for gatherings, not regularly accessed by students, but not restricted. What I found documented a pattern three separate sources had independently described: evidence that cafeteria workers had been sleeping there.

On the right side of the stage, in a preparation area, I photographed flattened cardboard boxes bearing the unmistakable impressions of repeated use as bedding. Nearby sat bottles filled with cigarette butts. Finished takeaway food containers were scattered across surfaces. Most telling: underwear belonging to cafeteria workers—middle-aged and older staff members, typically in their 50s and 60s—hung drying on the railings.

Multiple cafeteria workers, students who had previously accessed the space, and teachers all confirmed independently that this had been happening at least since 2023. I cannot confirm whether it continues today. But that workers at a school generating nearly over 210 million yuan in annual tuition revenue were sleeping on cardboard in a food preparation facility—even if it happened only in the past—reveals institutional priorities as clearly as any budget document.

The school takes pride in operating its cafeteria directly rather than contracting to outside companies, emphasizing in promotional materials that "everyone in the school eats the same thing" and highlighting food security. This is, genuinely, better than many international schools' approach. But operating the cafeteria in-house means the school bears direct responsibility for worker conditions. And the evidence suggests that while the institution invests millions in technological showpieces, the people who prepare food for 3,000 students may have lacked basic dignified housing.

The school's promotional materials claim to offer “financial support to students in need as well as scholarship opportunities.” In my six years at Xiwai—attending since Grade 5, deeply involved in student leadership, with extensive networks across grade levels—I have never heard of a single student receiving such support. If such a program exists, it operates in such obscurity that it might as well not exist. For an institution generating nearly 210 million yuan in revenue annually, the absence of visible, accessible financial aid reveals priorities: invest in spectacle for recruitment, starve resources that actually serve students and teachers.

The school's promotional materials claim to offer “financial support to students in need as well as scholarship opportunities.” In my six years at Xiwai—attending since Grade 5, deeply involved in student leadership, with extensive networks across grade levels—I have never heard of a single student receiving such support. If such a program exists, it operates in such obscurity that it might as well not exist. For an institution generating nearly 210 million yuan in revenue annually, the absence of visible, accessible financial aid reveals priorities: invest in spectacle for recruitment, starve resources that actually serve students and teachers.

IX. What Needs to Happen

What needs to happen is both simple and profound.

Immediate accountability: The school must formally acknowledge that Mr. Zheng's conduct during the SLO election violated established student governance procedures and constituted abuse of authority. This doesn't require termination, but does require public acknowledgment and a clear message that such behavior won't be tolerated. The SLO Constitution must be restored as the governing document for student organization elections, with explicit administrative commitment to non-interference.

Mental health infrastructure: Hire at minimum two additional full-time counselors dedicated solely to student mental health, bringing ratios closer to professional association recommendations of 1:150 or lower for mental health specialists. At market rates for licensed mental health professionals in Shanghai (approximately 200000-300000 yuan annually), two additional counselors would cost 400000-600000 yuan per year—less than the robot dog purchase, and sustainable given the school's nearly 200-million-yuan annual revenue. These counselors should not teach classes. Their sole responsibility should be student well-being.

Professional college counseling: Hire at least two additional professionally trained college counselors to bring the ratio closer to industry standards of 1:100 for college advising. At approximately 250000-350000 yuan per counselor annually, this represents an investment of 500000-700000 yuan—again, less than the holographic projection system, and essential for students navigating one of life's most consequential decisions.

Structural reforms: Publish annual summaries of tuition revenue allocation across major budget categories so parents and students understand how their nearly 210 million yuan in combined tuition is spent. I

mplement baseline standards for faculty resources—including basic equipment like printers—that don't require contractual negotiation. A one-time investment of 100000 yuan would provide printers for every teacher who needs one; annual maintenance costs would be negligible. Hire professional marketing and communications staff with quality standards and strategic oversight.

Allocate resources for a modern, functional website—a well-designed institutional website costs 50000-100000 yuan to develop and perhaps 20000 yuan annually to maintain, a fraction of one percent of annual revenue.

Require all administrators to complete professional training in recognizing, accommodating, and responding to student mental health needs, including understanding of somatic symptoms.

Cultural accountability: The school must recognize its integrity is measured not by technology displayed on campus tours, but by how it treats students in crisis, teachers seeking basic resources, and families trusting it with their children's education and financial resources.

The school must realize, that strong enrollments come with a high-quality school with an innovative setting and dedication to do real, meaningful things for the students. Sending out fake advertisements isn’t the solution to all-time-low admission and student attention rate; improving is. As the old Chinese idiom goes: 授人以鱼不如授人以渔, teaching a person how to fish is better than giving the person a fish. The so-called useful “walking course(tourism, essentially)”, unverified “innovative AI class”, and oral moral lecturing won’t capture the students and parents with real competitive edge, because they could see through the cover-up and the reality of this school. If Xiwai was really about educating the next-generation of leaders of our world, the school itself, then should at least act like one.

X. Why I'm Speaking

I'm aware that disclosing my mental health diagnosis may be used to discredit this reporting. That some may suggest my 'personal struggles' have distorted my perception of events. This is precisely why I've documented everything: the 10-page formal complaint filed in September, the constitutional violations cited, the financial data analyzed, the photographs taken, the multiple independent sources interviewed. This article presents verifiable facts that exist independently of my mental state. My diagnosis doesn't invalidate my reporting—if anything, it underscores the human cost of institutional failure.

I'm prepared for uncomfortable conversations, administrative pressure, and potential consequences. I'm speaking because I spent six years believing in Xiwai's stated mission, and I'm not willing to leave quietly while the institution betrays that mission for every student who comes after me.

I'm also aware that privilege allows me this risk. My family can afford tuition. My university applications are largely complete. I have recourse and resources many students don't. Which means I have a responsibility to use my position to speak for those who can’t.

To Students Reading This

If you're reading this and recognizing your own experiences—the anxiety, the institutional indifference, the sense of struggling alone—please know you're not alone, and it's not your fault. The system is broken. You are not broken. Seek professional help outside the school system if possible. Tongji Hospital has excellent psychiatric services. Document everything. Build community with peers. Find teachers and administrators you trust, because they exist even within broken systems.

To the Administration

To the administration: I don't believe everyone at Xiwai is complicit in these failures. I've been taught by extraordinary teachers. I've worked with administrators, including Principal Piccinini, who genuinely want to do right by students. But good individuals cannot compensate for systemic dysfunction. Institutional change requires accountability, resources, and willingness to prioritize students over appearances.

That's not too much to ask. You claim to offer international standards, holistic education, student-centered learning. You promise families a healthy and supportive environment. You have the resources and the revenue. What you lack is institutional will. This is your opportunity to prove me wrong.

XI. Living with the Aftermath

As I finish writing this, I'm four weeks into a new medication regimen. Some days are easier than others. Some days the symptoms break through anyway—the mood swings, the physical pain that has no physical cause, the occasional visual distortions that remind me my brain doesn't always process reality the way it should. I'm learning to live with this. I'm learning what recovery looks like when the thing that broke you is a place you still have to walk into every morning.

But I'm also learning something else. In the weeks since I started drafting this article, seven students have reached out to me privately. Some I knew. Some I didn't. All of them said some version of the same thing: “I thought it was just me. I thought I was the only one who felt this way.”

That's what institutional failure looks like at the individual level. Not dramatic collapse. Not obvious catastrophe. Just student after student, in separate rooms, separate crises, each one believing they are alone in their struggle against a system that should be supporting them.

Wanke Yang, whose story I told two years ago, once said: “I may have left Xiwai, but my journey is far from over. I will continue to speak out, to advocate for change, and to create a world where mental health is not a taboo, but a priority.”

I share that commitment. This article is part of that fight. Not because I expect immediate change. Not because I believe one piece of student journalism will suddenly make administrators choose differently. But because silence is complicity, and because the students who come after me deserve to know they're not alone when the institution fails them.

They deserve to know that when a school spends 3.3 million yuan on robot dogs and holographic projections but won't hire adequate counselors, that's not a budget constraint—it's a values statement. When administrators dismiss student governance and treat mental health crises with skepticism, that's not bureaucratic incompetence—it's institutional culture. When teachers can't get 300-yuan printers but the marketing budget runs to millions, that's not an accident—it's a choice.

And choices can be challenged. The students of Xiwai deserve a school that actually believes in us, that recognizes mental health support and basic resources aren't luxuries but fundamental requirements of genuine education. That's not too much to ask.

It's the minimum we should accept.

About the Author

Zihao Wang is a senior at Shanghai Xiwai International School and serves as editor-in-chief of The Magnolian, the school's student newspaper. He has been recognized for his investigative journalism on mental health issues in educational institutions.

If you are a current or former Xiwai student or staff member with experiences related to the issues discussed in this article, The Magnolian welcomes your perspective. Contact us confidentially through the editorial office at lettertoeditors@xiwaimoments.com.cn .

Editorial Standards Notice

This article reflects the documented experiences and investigative research of the author, who serves as Editor-in-Chief of The Magnolian.

Nature of this piece: This is a first-person investigative essay combining personal narrative with systematic documentation of institutional practices. The author was directly affected by events described and cannot claim detachment, but has maintained investigative rigor through:

-

Documentary evidence (formal complaints, photographs, financial records)

-

Multiple independent source verification

-

Citation of specific dates, amounts, and statements

-

Reference to applicable PRC laws and regulations

Verification: Factual claims have been verified through available documentation. The Magnolian stands behind the accuracy of reported facts while acknowledging this work represents one participant's perspective on systemic issues.

Legal notice: Named individuals are referenced in their official capacities as relevant to institutional accountability. This article exercises the student's right under Article 42 of the Education Law of the People's Republic of China to "lodge a complaint" regarding educational matters.